Archives division, Texas state library

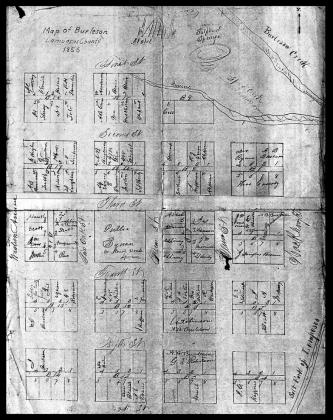

The 18-block subdivision map of Burleson, Texas survives in the holdings of the Texas State Library in Austin. Depicted on that map are the Scott Hotel or Tavern, and Scott’s White Sulphur Spring. According to the map, that structure was located west and north of the spring. Lots were set aside for a public square and jail. Depicted on a similar map, also found in possession of the TSL, is an expanded version of this subdivision. On this map, the Burlesons reserved a public highway or potential roadway to Scott’s mill between the subdivision and the north side of the Salt Fork of the Lampasas River, the stream we now call Sulphur Creek. The oldest map record of this subdivision in Lampasas is found in Volume T, page 73, of the Lampasas County Deed Records. It was filed on Feb. 12, 1890, and was based on G.W. and Elizabeth Scott’s map dated Feb. 6, 1860. The earlier map may have been destroyed in the courthouse fire of Christmas 1871. The TSL maps may be mis-filed pages from one of the old Burleson cases files.

BY JEFF JACKSON

SPECIAL TO THE DISPATCH RECORD

This story of history is the news 150 years too late, but when this story happened Lampasas did not have a newspaper to report it. This untold story is found in the deed records of the county. You cannot tell the history of Lampasas without mentioning the Burlesons. They created the sub-division and sold the first building lots in what would become the Lampasas community. There is no error in that. The error is in the omission of the rest of their story – what happened to them, and why they did not remain citizens of Lampasas longer. Before the publication of “Lamplights of Lampasas County” in 1951 and “Relighting Lamplights” in 1974, the earliest history of Lampasas was an untold story. Since then, “Lamplights” has become the guide that other writers and researchers have used for the myth of creation. If there was a college-level course titled “Lampasas History 101,” that is the story the professors would tell. It has become the folk legend of the creation of the Lampasas community.

ORIGINAL JOHN BURLESON SURVEY

The first houses and businesses of Lampasas were built on the John Burleson Survey. Originally called Burleson, the name of the town changed to Lampasas when the county was created. Nobody really knows where Moses Hughes, the man credited with being the first settler of the community, originally set up camp with his family in 1853, but it could have been on the John Burleson Survey. The survey got its name from Hopping John Burleson. John Burleson Jr. is the Burleson who, together with his children, came to Lampasas in 1854 and began planning and establishing a townsite that would become Lampasas. According to local legend, Elizabeth Scott and her husband George W. Scott laid out the first streets and blocks of the Lampasas community. John Gracy recalled, “G.W. Scott and John Burleson laid off the town of Lampasas in lots, and G.W. Scott and Elizabeth L. Scott sold them.” John’s son Jasper Gracy recalled that in 1855, he carried the stakes to drive down at the corners of the lots for his father, G.W. Scott and a surveyor from some other county. There were several John Burlesons in Texas. About the year 1837, Hopping John Burleson, an unlettered man of many eccentricities, brought his family to Texas and settled in Bastrop County. As “the head of a family,” Hopping John was entitled to a conditional certificate of 1,280 acres of land. John Burleson Jr. was the brother of Gen. Edward Burleson. The Burleson name carried prestige in Texas. Any prestige Hopping John Burleson and John Burleson Jr. might have garnered may have been lost in the pleadings and petitions taken to the Texas court system over the ownership of the 1,280-acre John Burleson Survey in what would become Lampasas County in the years to come. Hopping John’s land certificate was issued by the board of land commissioners of Bastrop County on April 26, 1838. On Sept. 13, 1838, Hopping John Burleson sold his conditional certificate for 1,280 acres of land to Samuel Colver for $300. On June 22, 1839, Samuel Colver located the land for Burleson’s land certificate and returned the field notes to the General Land Office. The settlement of Texas would not reach what became Lampasas until the 1850s. Colver left Texas and eventually settled in Oregon. A number of years passed before what would become Lampasas was on the frontier edge of settlement. Ignoring his previous sale to Colver, Hopping John sold his claim to the property a second time. On July 12, 1854, he delivered a deed of assignment for the conditional certificate to John Burleson Jr. In 1855, John Burleson Jr., his daughter Elizabeth Scott and her husband George Scott laid out a townsite and sold various lots and parcels of land. That subdivision is now called “The Old Town of Lampasas.” Unbeknown to the purchasers of various lots and parcels out of the Burleson Survey, the Burlesons did not have a clear title to the land they were selling.

SUIT FILED AGAINST BURLESONS

The Lampasas community was only three or four years old when Colver filed suit against the Burlesons. Samuel Colver sold his claim to the John Burleson Survey to William Colver on Aug. 31, 1858, for $10,000, and on Sept. 3, 1858, William T. Colver filed suit against the Burlesons in the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas, in Austin. The plaintiff, William T. Colver, complained that Hopping John Burleson and John Burleson Jr. worked together to defraud Samuel Colver out of the 1,280 acres of land in controversy. The cases would take 12 years to resolve. The final decision would not be reached until after the Civil War was over and Reconstruction was nearing an end. The Civil War wrecked the Texas economy, and property values crashed. William Colver sold his legally entangled title to Robert T. Storm, the son of William H. Storm for $3,000 (2,000 gold coin dollars) on May 27, 1867. On July 10, 1868, Robert Storm sold the Colver title to Tillman Weaver for $500. There were two transaction involving Robert T. Storm on May 27,1867. He sold the former Scott Hotel and spring property to John L. Hanna and his sister Isabell, and he purchased the still-in-litigation Colver title from William T. Colver. He must have had confidence that the Colver title complaint eventually would end up in Colver’s favor. One year later he sold the title to Tillman Weaver. Weaver would be the ultimate winner. The Storm family packed up and headed for California. Robert died of smallpox before getting there. In 1880, Tillman Weaver sold the lots set aside on the original subdivision map for a jail and a public square to the county for token fees of $10 each. The Burlesons were also slave owners. In 1860, John had one slave, and his son-in-law Robert J. Moore had four slaves. Hopping John Burleson had seven slaves. Now living in Lamar County, George W. Scott had 15 slaves. The fabled Scott Hotel was built with slave labor. If the slaves represented wealth, then the Civil War would change all of that.

COURT JUDGMENT HANDED DOWN

On Jan. 10, 1870, the Chancery Court handed down a judgment in favor of Colver and against the Burlesons. It all boiled down to this: “Having fully considered the bill and answer and proof in this case together with the briefs furnished by the solicitors on both sides, and the authorities referred to by them, my conclusion is that the defendants do not occupy the position of innocent purchasers for a valuable consideration, without notice, and that the complainant has established his right and title to the land sued for, as against the defendants, excepting so far as they may be protected by the Texas Statutes of Limitation of three years.” There might have been a simpler way to say all this, but that is typical of the language judges and lawyers use. This judgment excluded tenants who had purchased sections of the land in controversy and proved three years’ possession, which entitled them to keep the property they had purchased, occupied, and built homes and businesses on. In another legal matter, Hopping John’s children filed suit against John Burleson Jr., titled Burleson v. Burleson. The list of defendants included John Burleson Jr., George W. Scott and his wife Elizabeth, Robert J. Moore and his wife Martha J., and A.B. Burleson. The list of co-defendants included on the complaint were John Hoffman, Jesse Eaton, Thomas Tate, Jacob Tinbrook, Robert Murray, Christopher Quesenberry, Jesse Weaver, John S. Stump, Joseph A. McMurray, John Evans, Benjamin French, Riley Cross, John Z. Bean, S.F. Mains, Joseph Mains, Stephen Boyce, Docus Williams, James Gibson, Jesse Eaton, Samuel Parker, John M. Rae, Charles Mullins, William B. Covington, James M. Cross, Pacton Gibson, Dr. Wales, J. Douglass Brown, Tilman Weaver, A.W. Anderson, Squire Fletcher, E.E. Stewart, E.W. Holler, W.C. Wisemen, M.D. Sherman, John M. Forehand, B.S. Whitaker, Elkanah Quesenberry, Thomas B. Huling, Moses Hughes, Samuel Wheat, Mary M. Burleson, E.L. Lindsay, A.B. Scallin, John H. Fulk, L.K. Miller, T.T. Bailey, John Dunn, J.C. Higgins, Enoch Powell, T.J. Laughlin, J.W. Murrell, G.H. Coleman, R.H. Flanagin, David Love, D.W. Stewart, John Blair, Henry Cook, William Oliphant, H. Stencey, J.M. Litton, Edward Christian, P.A. Monroe, A.J. Horne, A.O. Horne and Fanny M. Foster. The co-defendants included everyone who had purchased property out of the John Burleson Survey. They were the original property-owning settlers of the Lampasas community. When it came to the Burlesons, the court reporter noted that: “The parties to this suit belong to a numerous, highly respectable and well-known family, somewhat famous, as well in [the] history of revolutionary and border warfare as in the reports of Texas litigation.” The court reporter also made note of the ponderous record and voluminous briefs the Burlesons had piled upon the court and wrote in the record that, “A detailed statement of the pleadings and evidence would tend rather to confuse than to enlighten the mind of the reader.” And, after “one hundred and thirty pages of pleadings,” the judge who delivered the opinion declined to make any critical analysis of them. There was “nothing left to the losing party, except to abuse the court for not finding out that which he has himself effectually obscured.” The court ruling favored John Burleson Jr. The court had 132 pages of material to contend with in Burleson v. Burleson. The other two case files used to tell this story were much longer. Colver v. Burleson is 296 pages long, and Burleson v. Hanna is 333 pages long. On March 10, 1856, Andrew Bell Burleson (the son of John Burleson Jr.) was elected first chief justice of Lampasas County and remained in office until Sept. 21, 1857. He became a candidate for the Texas Legislature in July 1857. He withdrew as a candidate for the legislature when someone noted he had not settled his account with the comptroller’s office when he was the tax-assessor/ collector of Travis County in 1854. On Sept. 26, 1857, Bell Burleson shot a man named Joel Franklin. Franklin filed suit against Burleson for the injuries caused by the shotgun blast. The result of that suit is unknown. Bell returned to Travis County before the 1860 census. He was a colonel in Parson’s Texas Cavalry during the Civil War. He drank too much. He was placed in the Austin lunatic asylum in 1873 and died there on April 21, 1874. The Burlesons began leaving Lampasas before a legal decision against them was rendered in the Chancery Court. John Burleson’s struggle to maintain ownership of the land was futile. He returned to Travis County before 1870, and died there on March 30, 1874. John and his son, Andrew Bell Burleson, are buried in the Old Burleson-Rogers Cemetery near Hornsby Bend of the Colorado River on the east side of the ever-expanding city of Austin.

OTHER BURLESON TROUBLEMAKERS

Bell was not the only trigger man in the Burleson family. His brother, John Tyler Burleson, shot and killed Clinton Hurley with a six-shooter on Oct. 6, 1861 in Lampasas. Fearing mob violence, Burleson headed for parts unknown. He ventured back to Lampasas in 1867 and married Mary Rebecca Hill. At that time, he was described as a desperate man who had 16 indictments against him for capital offenses. He was arrested and taken to the McLennan County jail for safe keeping. John T. escaped from that facility on June 25, 1867. The governor of Texas offered a $300 reward for his arrest and delivery. A description of the wanted man said Burleson was a gambler about 23 years of age. He stood six feet two inches tall, had a fair complexion, auburn hair, blue eyes and weighed about 175 pounds. In October, Lampasas County Sheriff William Hurley, brother of the man Burleson killed in 1861, informed Texas Gov. Elisha M. Pease that Burleson was near Moralis, Mexico. How he met his end is unknown. According to Find A Grave .com, John Tyler Burleson (1845-1871) is buried in the Old Burleson-Rogers Cemetery.

PROBLEMS FOR ELIZABETH BURLESON SCOTT

George and Elizabeth Scott moved to Lamar County before 1860. On May 21, 1863, they sold the Scott’s White Sulphur Spring and Scott Hotel to William H. Storm and Thomas J. “Boot” Moore for $4,000. Storm was the chief justice (equivalent of the county judge) of Lampasas County from 1864-1866. The Scotts’ marriage would not last much longer than that. On Sept. 21, 1867. Elizabeth L. Scott filed suit against John L. Hanna; her husband, George W. Scott; and others over the ownership of the Scott Hotel and Scott’s White Sulphur Springs. The case was not decided until May 10, 1876. This was quite a colorful case. The Burlesons claimed Elizabeth Scott had been afflicted with physical and mental problems since age 16. She used drugs (opium or morphine) in combination with alcohol in excess to relieve her physical abnormalities and mental alienation. The Burlesons tried to prove that Elizabeth Scott was not sober when she signed the deed to Scott’s White Sulphur Springs over to William H. Storm and Thomas J. Moore. The Burlesons claimed her husband George W. Scott and William T. Storm worked together to swindled her out of her property. According to Burleson, when the money ran out, George Scott abandoned his wife and disappeared into oblivion. William H. Storm was in financial trouble, and the former Scott property was put in his son’s name in order to protect his assets from his creditors. On May 27, 1867, Robert Storm sold the property to John L. Hanna and his sister Isabella Hanna. The Hannas would deny any knowledge of, or participation in fraud, collusion, conspiracy or confederation against the plaintiff Elizabeth Scott. They were innocent purchasers of the land and paid for it in good faith and valuable consideration. John Gracy told the court he heard Elizabeth Scott boast she was smart, shrewd and sensible. He heard her say she was a Burleson, and Burlesons were smart at law. Gracy concluded his statement by saying, “I do hope that she may be defeated in her suit and have so expressed myself.” Gracy was there when the first sub-division of the John Burleson Survey was staked off into streets and building lots in 1855. He later went on to build the Star Hotel, which became the Keystone Hotel. All the legal finagling had not garnered the Burlesons any friends. Elizabeth Scott may have been delusional or misguided when she claimed that Burlesons were smart and shrewd at law. She later returned to Travis County. Her probate record is dated Oct. 21, 1872. She left her entire estate to her father. All she had was the 50 acres of land including the Scott Hotel in Lampasas, and that was tied up in a lawsuit with John L. Hanna and his sister Isabell. In the end she had nothing.

FOUNDERS OF LAMPASAS

John Burleson Jr. and his children really were the founders of the Lampasas community. We could easily forget everything else they did along the way and let the stories surrounding them stay in obscurity. It all happened so long ago, and eventually all the legal matters that surrounded them were sorted out one way or another. Today, the Burlesons are remembered as the founders of the Lampasas community and not fraudulent land speculators. The Burleson name remains on a small creek that runs through the Lampasas community. Anybody driving north on Key Avenue out of Lampasas will pass over it, but rarely will anyone notice the name of the small creek. The Burlesons established a town when they subdivided a small portion of the John Burleson Survey and offered lots out of it for sale. The first sub-division of Lampasas was measured off in 1855. It consisted of 18 blocks and a public square. It was bound by First Street on the north, Hackberry on the east, Sixth Street on the south, and Western Avenue on the west. Western Avenue was also the west line of the John Burleson Survey. The east-west streets were numbered First through Sixth, and the north-south streets were named after trees: Hackberry, Elm, Pecan and Live Oak. There was no city government and no zoning laws to regulate the development of the frontier community. The town grew slowly, and in 1873 the Texas Legislature created the first City of Lampasas and established the first city limits. The aldermen passed a tax ordinance and maintained city offices until 1876, when the city government was allowed to lapse. Why? Maybe the people of Lampasas did not like paying city taxes. The records of the first city councils of Lampasas were never preserved. In 1883, the city re-established itself and began electing a mayor and aldermen once again, but that is another story.

A LESSON FOR THE HISTORY BOOKS

Our heritage is based on the good and the bad, but we do not live in a fantasy world where everything is always good. Which part of our history do we chose to remember? Only the good things? Should we leave the unpleasantries out and base our history on the omission of facts? History is a part of our evolutionary process. If we cannot learn from our past, then we cannot learn and are destined to repeat it. We did learn from it, and today we have title insurance to protect and guarantee our land sales.

SOURCES:

1. Burleson v. Burleson. Reports of Cases Argued and Decided in the Supreme Court of the State of Texas during the Austin Session, 1866, Volume XXVIII, and covers pages 383-419. Archives Division, Texas State Library.

2. United States District Court Western District of Texas at Austin. No. 15. William T. Colver vs. John Burleson Sr. of Gonzales; John Burleson Jr. of Lampasas; Andrew B. Burleson; George W. Scott and Elizabeth L. Scott; and Robert J. Moore and Martha Jane Moore. The original papers are at the National Archives in Fort Worth, Texas.

3. M6930. No. 1925. Elizabeth L. Scott vs. John L. Hanna; Geo. W. Scott et.al., Lampasas Co. Decided [May 10,] 1876. The original case file is in the holding of the Archives Division of the Texas State Library.

4. Other materials came from the Lampasas County Deed Records (mostly Volume A) and various Texas newspapers.